- Home

- Slavoj Zizek

Zizek's Jokes

Zizek's Jokes Read online

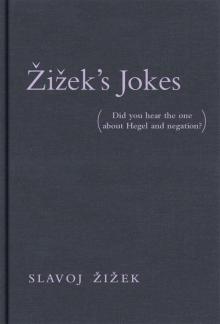

Žižek’s Jokes

Žižek’s Jokes

(Did you hear the one

about Hegel and negation?)

SLAVOJ ŽIŽEK

EDITED BY AUDUN MORTENSEN

AFTERWORD BY MOMUS

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

© 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

This edition is based upon an earlier publication, The Collected Jokes of Slavoj Žižek, published by Flamme Forlag, © 2012 Audun Mortensen.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected].

The image on page 135 was created by Sean Reilly.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Žižek, Slavoj.

Žižek’s jokes : (did you hear the one about Hegel and negation?) / by Slavoj Žižek ; edited by Audun Mortensen ; afterword by Momus.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-262-02671-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Wit and humor—Philosophy. 2. Wit and humor—Psychological aspects. 3. Philosophy—Humor. 4. Joking—Psychological aspects. I. Mortensen, Audun. II. Title.

PN6149.P5Z59 2013

808.87—dc23

2013019607

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Instead of Introduction:

The Role of Jokes in the Becoming-Man of the Ape

Žižek’s Jokes

Afterword by Momus

Bibliography

About the Contributors

INSTEAD OF INTRODUCTION:

THE ROLE OF JOKES IN THE BECOMING-MAN OF THE APE

One of the popular myths of the late Communist regimes in Eastern Europe was that there was a department of the secret police whose function was (not to collect, but) to invent and put in circulation political jokes against the regime and its representatives, as they were aware of jokes’ positive stabilizing function (political jokes offer to ordinary people an easy and tolerable way to blow off steam, easing their frustrations). Attractive as it is, this myth ignores a rarely mentioned but nonetheless crucial feature of jokes: they never seem to have an author, as if the question “who is the author of this joke?” were an impossible one. Jokes are originally “told,” they are always-already “heard” (recall the proverbial “Did you hear that joke about …?”). Therein resides their mystery: they are idiosyncratic, they stand for the unique creativity of language, but are nonetheless “collective,” anonymous, authorless, all of a sudden here out of nowhere. The idea that there has to be an author of a joke is properly paranoiac: it means that there has to be an “Other of the Other,” of the anonymous symbolic order, as if the very unfathomable contingent generative power of language has to be personalized, located into an agent who controls it and secretly pulls the strings. This is why, from the theological perspective, God is the ultimate jokester. This is the thesis of Isaac Asimov’s charming short story “Jokester,” about a group of historians of language who, in order to support the hypothesis that God created man out of apes by telling them a joke (he told apes who, up to that moment, were merely exchanging animal signs, the first joke that gave birth to spirit), try to reconstruct this joke, the “mother of all jokes.” (Incidentally, for a member of the Judeo-Christian tradition, this work is superfluous, since we all know what this joke was: “Do not eat from the tree of knowledge!”—the first prohibition that clearly is a joke, a perplexing temptation whose point is not clear.)1

NOTE

1. Less Than Nothing (London: Verso, 2012), 94–95.

ŽIŽEK’S JOKES

THREE WHITES AND TWO BLACKS

We should reread Lacan’s text on logical time, where he provides a brilliant interpretation of the logical puzzle of three prisoners. What is not so well known is that the original form of this puzzle comes from the eighteenth-century French libertinage with its mixture of sex and cold logic (which culminates in Sade). In this sexualized version, the governor of a woman’s prison has decided that he will give amnesty to one of the three prisoners; the winner will be decided by a test of her intelligence. The three women will be placed in a triangle around a large round table, each naked from the waist below and leaning forward on the table to enable penetration a tergo. Each woman will then be penetrated from behind by either a black or a white man, so she will be only able to see the color of the men who are penetrating the other two woman in front of her; all that she will know is that there are only five men available to the governor for this experiment, three white and two black. Given these constraints, the winner will be the woman who first can establish the color of skin of the man fucking her, pushing him away and leaving the room. There are three possible cases here, of increasing complexity:

In the first case, there are two black men and one white man fucking the women. Since the woman fucked by a white man knows that there are only two black men in the pool, she can immediately rise and leave the room.

In the second case, there is one black man and two white men doing the fucking. The two women fucked by white men can hence see one white man and one black man. The woman fucked by a black man can see two white men, but—since there are three white men in the pool—she also cannot immediately rise. The only way for a winner to emerge in this second case is if one of the two women being fucked by a white man reasons in this way to herself: “I can see one white man and one black man, so the guy fucking me might be white or black. However, if my fucker was black, the woman in front of me fucked by a white man would see two black men and immediately conclude that her fucker was white—she would have stood up and moved immediately. But she hasn’t done this, so my fucker must be white.”

In the third case, each of the three women is being fucked by a white man, so that each of them accordingly sees two other white men. Each can accordingly reason in the same mode as the winner in case 2 had, in the following way: “I can see two white men, so the man fucking me can be white or black. But if mine was black, either of the two others could reason (as the winner in 2 does): ‘I can see a black man and a white man. So if my fucker is black, the woman fucked by a white man would see two black man and immediately conclude that her fucker was white and leave. But she hasn’t done this. So my fucker must be white.’ But since neither of the other two has stood up, my fucker must not be black, but white too.”

But here logical time enters. If all three women were of equal intelligence and indeed arose at the same time, this would cast each of them into a radical uncertainty about who is fucking them. Why? Each woman could not know whether the other two women have stood up as a result of going through the same reasoning process she has gone through, since she was being fucked by a white man; or whether each had reasoned as the winner in the second type of case had, because she was fucked by a black man. The winner will be the woman who will be the first to interpret this indecision correctly and jump to the conclusion that it indicates how all three were being fucked by white men.

The consolation prize for the other two women will be that at least they will have been fucked to the end, and this fact gains its meaning the moment one takes note of the political overdetermination of this choice of men: among the upper-class ladies in the mid-eighteenth-century France, black men as sexual partners were, of course, socially unacceptable, but coveted as secret lovers because of their alleged higher potency and supposedly extra-large penises. Consequently, to be

fucked by a white man means socially acceptable but intimately not-satisfying sex, while to be fucked by a black man means socially inadmissible but much more satisfying sex. However, this choice is more complex than it may appear, since, in sexual activity, the fantasy gaze observing us is always here. The message of the logical puzzle thus becomes more ambiguous: the three women are observing each other while having sex, and what they have to establish is not simply “Who is fucking me, a black or a white guy?” but, rather, “What am I for the Other’s gaze while I am being fucked?,” as if her very identity is established through this gaze.

THE FUNCTION OF REPETITION is best exemplified by an old joke from Socialist times about a Yugoslav politician on a visit to Germany. When his train passes a city, he asks his guide: “What city is this?” The guide replies: “Baden-Baden.” The politician snaps back: “I’m not an idiot—you don’t have to tell me twice!”

A SNOBBISH IDIOT goes to an expensive restaurant and, when asked by the waiter: “Hors d’oeuvre?,” he replies: “No, I am not out of work, I earn enough to be able to afford to eat here!” The waiter then explains he means the appetizer and proposes raw ham: “Du jambon cru?” The idiot replies: “No, I don’t believe it was ham I had the last time here. But OK, let’s have it now—and quickly, please!” The waiter reassures him: “J’ai hâte de vous servir!” to which the idiot snaps back: “Why should you hate to serve me? I will give you a good tip!” And so on, till finally the idiot gets the point that his knowledge of French is limited; to repair his reputation and prove that he is a man of culture, he decides, upon his departure late in the evening, to wish the waiter good night not in French—“Bonne nuit!”—afraid that something might go wrong again, but in Latin: “Nota bene!”

Do most of the dialogues in philosophy not function in a similar way, especially when a philosopher endeavors to criticize another philosopher? Is not Aristotle’s critique of Plato a series of “Nota bene!” not to mention Marx’s critique of Hegel, etc., etc.?

ONE CAN WELL IMAGINE a truly obscene version of the “aristocrats” joke that easily beats all the vulgarity of family members vomiting, shitting, fornicating, and humiliating each other in all possible ways: when asked to perform, they give the manager a short course in Hegelian thought, debating the true meaning of the negativity, of sublation, of absolute knowing, etc., and, when the surprised manager asks them what is the name of the weird show, they enthusiastically reply: “The Aristocrats!” Indeed, to paraphrase Brecht’s quote “What is the robbing of a bank compared to the founding of a bank?”: what is the disturbing shock of family members shitting into one another’s mouth compared to the shock of a proper dialectical reversal? So, perhaps, one should turn the title of the joke around—the family comes to the manager of a night club specialized in hard-core performances, performs its Hegelian dialogue, and, when asked what is the title of their strange performance, enthusiastically exclaims: “The Perverts!”

THERE IS A NICELY VULGAR JOKE about Christ: the night before he was arrested and crucified, his followers started to worry—Christ was still a virgin; wouldn’t it be nice to have him experience a little bit of pleasure before he dies? So they asked Mary Magdalene to go to the tent where Christ was resting and seduce him; Mary said she would do it gladly and went in, but five minutes later, she ran out screaming, terrified and furious. The followers asked her what went wrong, and she explained: “I slowly undressed, spread my legs and showed Christ my pussy; he looked at it, said ‘What a terrible wound! It should be healed!’ and gently put his palm on it.”

So beware of people too intent on healing other people’s wounds—what if one enjoys one’s wound? In exactly the same way, directly healing the wound of colonialism (effectively returning to the precolonial reality) would have been a nightmare: if today’s Indians were to find themselves in precolonial reality, they would have undoubtedly uttered the same terrified scream as Mary Magdalene.

THERE IS A NICE JOKE ABOUT JESUS CHRIST: in order to relax after the arduous work of preaching and performing miracles, Jesus decided to take a short break on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. During a game of golf with one of his apostles, there was a difficult shot to be performed; Jesus did it badly and the ball ended up in the water, so he did his usual trick: he walked on the water to the place where the ball was, reached down and picked it up. When Jesus tried the same shot again, the apostle told him that this is a very difficult one—only someone like Tiger Woods can do it; Jesus replied, “What the hell, I am the son of God, I can do what Tiger Woods can do!” and took another strike. The ball again landed in the water, so Jesus again took a walk on the surface of the water to retrieve it. At this point, a group of American tourists walked by and one of them, observing what was going on, turned to the apostle and said: “My god, who is this guy there? Does he think he is Jesus or what?” The apostle replies: “No, the jerk thinks he is Tiger Woods!”

This is how fantasmatic identification works: no one, not even God himself, is directly what he is; everybody needs an external, decentered point of identification.

THERE ARE THREE REASONS we can be sure that Jesus Christ came from a Jewish family: (1) He took over the profession of his father; (2) his mother thought her son was a god; (3) he couldn’t imagine his parents had sexual relations.

HOW CAN WE BE SURE that Judas didn’t really betray Jesus Christ? Whatever one thinks about the Jews, they know the value of the things they sell, so no Jew would have sold a god for mere 30 silver talents!

IN THE MID-1930S, a debate is raging in the Politburo of the Bolshevik : will there be money in communism or not? The Leftist Trotskytes claim there will be no money since money is only needed in societies with private ownership, while the Rightist partisans of Bukharin claim that of course there will be money in communism since every complex society needs money to regulate the exchange or products. When, finally, Comrade Stalin intervenes, he rejects both the Leftist and the Rightist deviations, claiming that the truth is a higher dialectical synthesis of the opposites. When other Politburo members ask him how this synthesis will look, Stalin calmly answers: “There will be money and there will not be money. Some will have money and others will not have it.”

THE CRUCIAL SHIFT in the “negation of negation” is thus an unexpected change of the very terrain—this change undermines the position of the subject, involving him in the action in a new and much more direct way. Here is a nice case of such a change: at a local Communist Party meeting in Moscow, Petrov is delivering an interminable report. When he notices an obviously bored man in the first row, he asks him: “Hey, you, do you know who this Bulianoff I was just talking about is?” “No idea who he is,” answers the man, and Petrov snaps back: “You see, if you were to come to the party meetings more often and listen more carefully, you would have known who Bulianoff is!” The man snaps back: “But do you, Petrov, know who Andreyev is?” Petrov replies: “No, I don’t know any Andreyev.” The man calmly concludes: “If you were to attend the party meeting less often and listen more carefully to what is going on in your home, you would have known that Andreyev is the guy who is fucking your wife while you are delivering your boring speeches!”

A SIMILAR UNEXPECTED TURN toward vulgarity is enacted in the joke from the mid-1990s celebrating Bill Clinton’s seductive capacity: Clinton and the pope die on the same day; however, owing to the confusion in the divine administration, Clinton ends up in heaven and the pope in hell. After a couple of days, the mistake is noticed and the two are ordered to exchange places; they briefly meet in front of the elevator that connects heaven and hell. Upon seeing Clinton on his way from heaven, the pope asks him: “Tell me, how is the Virgin Mary? I cannot wait to meet her!” Clinton replies with a smile: “Sorry, but she is no longer a virgin.”

THE MEANING OF A SCENE can change entirely with the shift in the subjective point, as in a classic Soviet joke in which Brezhnev dies and is taken to Hell; however, since he was a great leader, he is given the privilege to be taken o

n a tour and select his room there. The guide opens a door and Brezhnev sees Khruschev sitting on a sofa, passionately kissing and fondling Marilyn Monroe in his lap; he joyously exclaims: “I wouldn’t mind being in this room!” The guide snaps back: “Don’t be too eager, comrade! This is not the room in hell for Khruschev, but for Marilyn Monroe!”

A JOKE FROM THE EARLY 1960S nicely renders the paradox of the presupposed belief. After Yuri Gagarin, the first cosmonaut, made his visit to space, he was received by Nikita Khruschev, the general secretary of the Communist Party, and told him confidentially: “You know, comrade, that up there in the sky, I saw heaven with God and angels—Christianity is right!” Khruschev whispers back to him: “I know, I know, but keep quiet, don’t tell this to anyone!” Next week, Gagarin visited the Vatican and was received by the pope, to whom he confides: “You know, holy father, I was up there in the sky and I saw there is no God or angels …” “I know, I know,” interrupts the pope, “but keep quiet, don’t tell this to anyone!”

ONE CAN EVEN DEVELOP into a Hegelian triad the lines from Psalm 23:4: “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me.” Its first negation would have been a radical reversal of the subjective position, as in the ghetto-rapper-version: “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for I am the meanest motherfucker in the whole valley!” Then comes the negation of negation that changes the entire field by way of “deconstructing” the opposition of Good and Evil: “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for I know that Good and Evil are just metaphysical binary opposites!”

THE LOGIC OF THE HEGELIAN TRIAD can be perfectly rendered by the three versions of the relationship between sex and migraines. We begin with the classic scene: a man wants sex with his wife, and she replies: “Sorry, darling, I have a terrible migraine, I can’t do it now!” This starting position is then negated/inverted with the rise of feminist liberation—it is the wife who now demands sex and the poor tired man who replies: “Sorry, darling, I have a terrible migraine …” In the concluding moment of the negation of negation that again inverts the entire logic, this time making the argument against into an argument for, the wife claims: “Darling, I have a terrible migraine, so let’s have some sex to refresh me!” And one can even imagine a rather depressive moment of radical negativity between the second and the third versions: the husband and the wife both have migraines and agree to just have a quiet cup of tea.

Demanding the Impossible

Demanding the Impossible Zizek's Jokes

Zizek's Jokes Comradely Greetings

Comradely Greetings